A taxing time for legacy pensions

While the transfer balance cap rules can be harsh on legacy pensions, some careful planning can help to mitigate some of the more significant tax consequences of the new rules.

The way legacy pensions can be managed will be different depending on whether the effective implementation date of the change is before or after 1 July 2017. Non-commutable legacy pensions such as Section 1.06(2) lifetime, Section 1.06(7) life expectancy and Section 1.06(8) market linked often have quite decent assets backing them. This is because many were set up to access higher reasonable benefit limits (RBLs). While RBLs are now defunct, there has been no opportunity granted by the government to tidy up these legacy products.

With the introduction of the $1.6 million transfer balance cap (TBC) limiting the tax exemption that applies to income from assets funding superannuation pensions, special rules had to be put in place for ‘capped defined benefit income streams’.

Before 1 July 2017, this includes all three types of pensions, but after that date it is only lifetime pensions and annuities. The TBC rules can be very harsh and generate a massive tax windfall for the government. The purpose of this article is to show that with careful planning, it is possible to mitigate some of that harshness.

Since capped defined benefit income streams can’t remedy a breach of TBC with a commutation, the modifications for these products result in certain amounts being included in personal assessable income or adjustments to tax offsets.

Let’s say Bruce, who is aged 72, has $3.7 million backing a lifetime pension paying him $200,000 in 2017-18 with 4.9 per cent per annum indexation in subsequent years. The regulations assign a value of 16 times this to be counted against the TBC – an arbitrary, and in many instances totally inappropriate, value.

However, ignoring that, we can see Bruce is way over the TBC and any account-based pensions will have to be commuted. More nasty ramifications creep in on the administration side, as it will be necessary to start deducting and remitting PAYG deductions from the lifetime pension payments.

What the government appears not to have recognised in the legislation is that there is currently a right to convert a lifetime pension to a market-linked pension or change the term of market-linked pension. This is how we manage changing client requirements and optimisation of the tax paid.

As the market-linked pension remains non-commutable after 1 July 2017, if the amount is above $1.6 million, it may not be possible after that date to make the change when a market-linked pension is no longer a capped defined benefit stream and so presumably needs to comply with the cap.

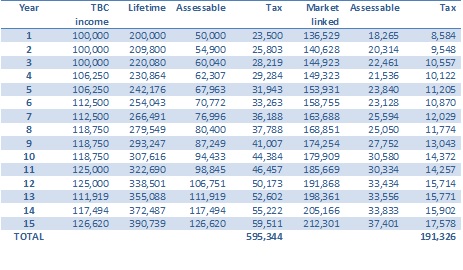

The issues can be clarified with an example. Hopefully, Bruce is not the ‘shoot the messenger’ type of person when told that over the next 15 years, roughly his life expectancy, he will pay about $595,343 in additional tax that he is not currently paying.

This is because 50 per cent of the pension payments in excess of $100,000 per annum (indexed) is added to his personal assessable income. If he is on a top marginal tax rate already, that is a lot of extra tax. Saying “tough, you’re rich and can afford it” may not be the best approach if you want to keep this client. Therefore, let’s see what can be done.

We need a strategy that will reduce pension payments that end up in assessable income and slow the rundown of exempt current pension income assets. We don’t have to worry about the retirement income Bruce wants to draw as this can be achieved via tax-free withdrawals from an accumulation account in many instances.

One way to reduce tax is to convert the 1.06(2) lifetime pension to a 1.06(8) market-linked pension with a long duration and utilise the minus 10 per cent drawdown variation that is allowed. The table shows total tax paid personally by both approaches if the marginal tax rate is 47 per cent. This may be higher with the announced Medicare levy changes.

This strategy results in tax savings on an undiscounted basis of $404,018. It also allows a higher average exempt current pension income over the years and a better reserving policy to be set up. One of the issues to be solved with a lifetime pension is how to use monies that are expected to be released to free surplus reserves when the pensioner passes away.

Estate planning preferences may cause a different solution to the above. There is a large element of personal preference in setting the optimal strategy. Often, an estate planning objective will be to avoid paying superannuation death benefit tax to financially independent children. It is simply an inheritance tax by a different name.

Individual circumstances can be far more complex than the above and each scenario requires careful analysis. There are still a number of issues where the regulator has been silent. One example is Section 1.06(6) flexi-pensions. To be prudent, one would imagine that TBC applies and commutation must be in line with Schedule 1B factors. To my knowledge, no material has been published so far by Treasury or the ATO on this aspect.

A far better solution would be to allow these legacy pensions to be commuted back to the $1.6 million cap and fix up the special value methodology shortcomings. I would go a step further and require all these legacy pensions to be converted into a standard account-based pension.

Our politicians and regulators have done Australia a great disservice by the level of complexity that is now built into superannuation regulation. While we are creating an understandable system for normal citizens, anomalies like different age pensions for a person who went on the age pension on 19 September 2016 versus 20 September 2016 can be added to the list.

In the absence of that simplicity, it is important to carefully consider how to make the 1 July 2017 TBC less taxing for clients and the regulators need to make clear whether they really mean a market-linked pension can never be changed or swapped to a new provider if it is above $1.6 million.

Brian Bendzulla, managing director, NetActuary